The US Solidarity Economy Network (USSEN) is a powerful force in social movements working toward cooperative and postcapitalist economies, democratic governance, social and racial justice, sustainability and climate justice, and electoral justice. For two decades, USSEN has consistently advanced a postcapitalist vision among a growing but fragmented movement for an economy for the 99%. USSEN is aligned with the international Solidarity Economy (SE) movement, in its commitment to a radical set of core values and the practices that help us live into these values.

The US Solidarity Economy Network (USSEN) is a powerful force in social movements working toward cooperative and postcapitalist economies, democratic governance, social and racial justice, sustainability and climate justice, and electoral justice. For two decades, USSEN has consistently advanced a postcapitalist vision among a growing but fragmented movement for an economy for the 99%. USSEN is aligned with the international Solidarity Economy (SE) movement, in its commitment to a radical set of core values and the practices that help us live into these values.

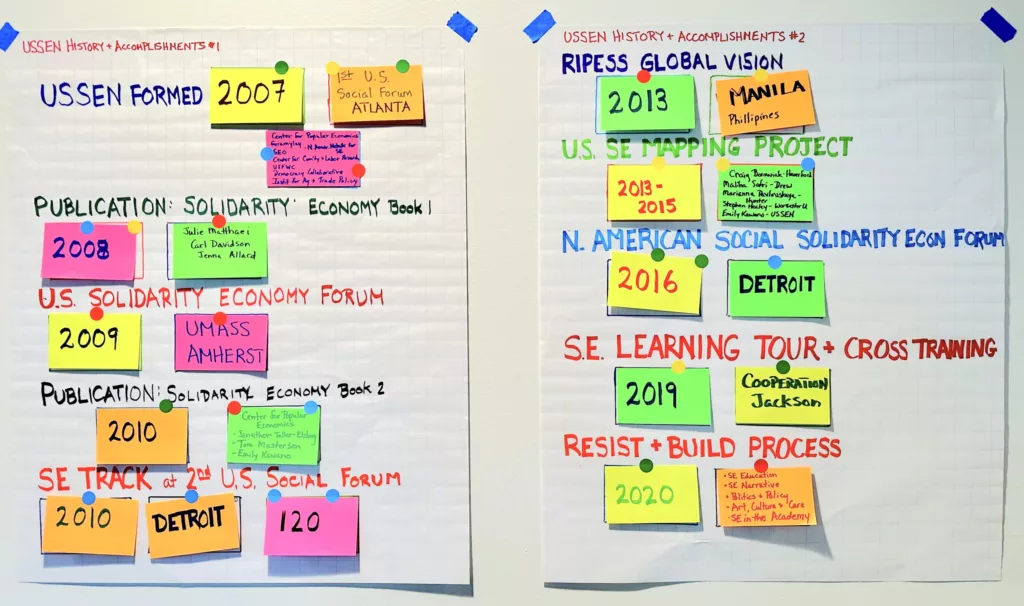

In this context, USSEN pursues a number of activities to organize and bring focus to the sometimes chaotic proliferation of economic justice projects, bringing SE values and practices to life through through educational offerings, strategic movement gatherings, storytelling efforts, and intentional movement relationship building and networking. USSEN acts as an umbrella where individuals and organizations in the network can move forward projects to advance SE work with support from the board and other members.

>> Check out our current Collaborations

Mission

Please note that this is a working document that is open for discussion, debate and change.

The mission of the U.S. Solidarity Economy Network is

- To connect a diverse array of individuals, organizations, businesses and projects in the shared work of building and strengthening regional, national and international movements for a solidarity economy. Through publications, a website, mailing list, and face-to-face gatherings, the network will facilitate: ongoing communication and dialogue relating to the development of solidarity economy ideas, values and practices; the sharing of experiences, models and skills; and the creation of collaborative, movement-building projects between network members.

- To join with and build the movement for transformative social and economic justice. To develop strong relationships and exchange between U.S. and global organizations, practitioners and solidarity economy networks such as RIPESS (Intercontinental Network for the Promotion of the Solidarity Economy) and RIPESS-N. America.

- To create a structure and vision that can promote a common identity and agenda among the currently fragmented elements of the U.S. solidarity economy. SEN will build a learning community on issues relevant to the solidarity economy, including discussing and debating strategies and practices, and helping each other to uphold the principles of the solidarity economy.

- To investigate and develop ways to build collaborative support systems for solidarity economy development. Examples might include: coordination between solidarity economy producers, suppliers and distributors; collaborative marketing, branding and/or distribution; group purchasing of insurance, energy, supplies; peer support & technical assistance.

- To raise the visibility, legitimacy and public support for solidarity economy practices through public education and media coverage. Examples might include: development of accessible educational materials and workshops for different sectors; SEN speakers ‘bureau;’ the development/implementation of a media strategy to “mainstream” the solidarity economy into public consciousness; dissemination of research among social movements and opinion-makers.

- To promote public policies and leverage resources for the support of the solidarity economy. Examples might include: loan fund for solidarity economy enterprises; reduction of barriers faced by ‘alternative’ forms of enterprise in terms of access to capital, tech. assistance, workforce development, etc.; tax incentives; support for research and dissemination; support for educational programs to train solidarity economy practitioners.

- To facilitate research on the scope, scale, and impacts of the solidarity economy; best practices; opportunities for cooperation; and the development of training and technical support resources. To contribute to new theories of economic development informed by the dynamism and innovative practices within the solidarity economy. This knowledge base will be used to support objectives 3-5.

Governance

The network is governed by a volunteer board representing Solidarity Economy movement organizations, plus two seats for individuals. Member organizations embrace the solidarity economy values, which includes democratic governance. USSEN tries to intentionally keep one member on the board to represent strategically aligned national SE coalitions such as NEC, MayFirst, and the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives. The board’s activities are pursued autonomously, cooperatively in decentralized circles. The USSEN Board has adopted the sociocratic method of governance. Meetings are facilitated by a rotating volunteer from the board. Agendas are planned by the co-coordinators, but agenda items, including those requiring decision-making, may be brought by any board member. Board members may suggest new board members to join at any time and existing board members consent to the addition of new members.

Proposals are made, a sociocratic round gives each board member a chance to respond, and a vote of consent is taken. If there are blocks, the board digs into the concerns – either during or after the meeting in circles – to develop proposals that can achieve consent. Circles (or committees) of the board that govern more specific tasks or projects are voluntary, as is the leadership of those circles. Board members and circles can and do overlap and engage other non-board members in SE efforts. Circles and their leadership forms when there is energy and capacity to move a project forward. This style works well with the all-volunteer, no-staff, low-budget structure of USSEN.

Current Board Members

David Cobb – Cooperation Humboldt

Emily Kawano – Wellspring Cooperative

Jeuji Diamondstone – Worcester SAGE (Solidarity & Green Economy)

Julie Matthaei

Kali Akuno – Cooperation Jackson

Jessica Forden – Solidarity Research Center

Lydia Lopez – California Community Land Trust Network

Matthew Slaats – VA Solidarity Economy Network

Melanie Bush – May First Movement Technology

Micky Metts – US Federation of Worker Cooperatives & Agaric

Mike Strode – Kola Nut Collaborative

Naveen Agrawal – California Public Banking Alliance

Ouree Lee – Participatory Budgeting Project

Terry Gibson – Massachusetts Solidarity Economy Network (MASEN)

Part-time Staff Support

David Ferris

USSEN Founding Article

U.S. Solidarity Economy Network is Born at the U.S. Social Forum 2007 (founding article)

Jenna Allard and Julie Matthaei, Guramylay: Growing the Green Economy

Most of the over 10,000 people who traveled to the first-ever U.S. Social Forum would consider ourselves activists, and most are acutely aware of the many systemic problems that our country faces, from increasing inequality and persistent poverty to environmental degradation, from a corrupt political system to an unjust war, from the continuing struggle with racism and sexism to the intolerant policies enacted against immigrants and gay / lesbian / trans-gendered people. We know these issues are present, but we tend to prioritize some over others, sometimes missing opportunities to form alliances with activists with similar values and different issues. Often we lose sight of the fact that “we are all in this together”.

The concept of the solidarity economy has the potential to unite these many progressive causes, not just annually in a certain physical location, but as part of a larger movement that recognizes the necessity of all types of transformative practice. At the first ever Social Forum in the United States, the Solidarity Economy Working Group for USSF2007 coordinated a track of workshops, and also convened caucuses to try to find ways to unite our common causes, and to build systemic economic transformation and strategic cooperation from the grassroots. The term “solidarity economy” is barely on the lips of activists in the U.S., even though the concept has inspired significant activism on all other continents. But the solidarity economy, which is more of a framework than a model, has great potential to link our many concerns about structural change, and to also strategically link organizing groups that are already engaged in transformative practices. The solidarity economy is held together by common values, such as cooperation, democracy, equality, justice, ecological sustainability, community, and respect for diversity. Ultimately, it is economics where human needs, human development, and solidarity form the center, instead of unfettered competition and an insatiable drive for profit.

The “Economic Alternatives and the Social/Solidarity Economy” activities at the U.S. Social Forum represented the culmination of months of work and collaboration by the Solidarity Economy Working Group. The Working Group involved a diverse coalition of academics, economists, grassroots organizers, and activists in the worker cooperative movement. Emily Kawano, Julie Matthaei, and Ethan Miller took the lead in the Working Group: Emily directs the Center for Popular Economics in Western Massachusetts, creating participatory workshops on neo-liberalism for activists; Julie, a professor of economics at Wellesley College, also works with Guramylay: Growing the Green Economy; and Ethan, from Maine, is involved in both Grassroots Economic Organizing and the Data Commons Project. Dan Swinney, from the Chicag-based Center for Community and Labor Research, works to promote the high road in business, government, and labor , and is co-founder of NANSE (North American Network for the Solidarity Economy). Another member, Jessica Gordon Nembhard, teaches at the University of Maryland, is affiliated with GEO, and additionally works with the Democracy Collaborative. Melissa Hoover directs the United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives, and Heather Schoonover works at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. Yvon Poirier of GESQ, Quebec’s Solidarity Economy Network, represented the Canadian experience in the group.

The Solidarity Economy Working Group organized a Solidarity Economy Caucus to which they invited activists from a broad range of organizations involved in economic transformation. The first caucus meeting, on the very first day of the Forum, was a time to meet one another, develop a shared knowledge base of Solidarity Economy concepts, values, principles, and practice, and then discuss some of the challenges and opportunities involved in creating a solidarity economy network in the United States. A key part of this meeting was presentations from leaders in the Latin American and Canadian about their well-established and vibrant social/solidarity economy movements, including Michael Lewis (CED, Canadian Community Economic Development Network), Éthel Côté (RIPESS, International Solidarity Economy Network), Nancy Neamtan (Social Economy Workshop/Chantier de L’economie Sociale, Quebec), Nedda Angulo Villareal (GRESP, Peru Solidarity Economy Network/Grupo Red de Economía Solidaria del Perú).

The Working Group also organized a block of 28 workshops, and a list of 53 associated workshops, which it printed up in a program. The content of the “Economic Alternatives and the Social/Solidarity Economy” workshops was exciting and diverse. In the first day of workshops, there were roundtable discussions about economic transformation in the United States, as well as presentations on everything from green building, to ethical consumption, to worker cooperatives. Many of these workshops were interactive, and posited the solidarity economy as a concrete alternative to low-road neo-liberal policies. On the second day of workshops, for instance, the Center for Popular Economics and Grassroots Economic Organizing hosted a session entitled “Building a Solidarity Economy from Real World Practices”. This workshop reinforced how intuitive, organic, and rich with shared meaning these solidarity values really are. After a basic introduction, descriptions of lots of different initiatives were circulated on index cards, and we discussed them in small groups. Aside from worker cooperatives, there were descriptions of non-profit groups, pushes for progressive policy initiatives, ethical consumption networks, and new sustainable technologies – constellations of different creative ideas from vastly different fulcrums of change. When it came time to construct a framework out of these practices and to name the implicit values, however, it was easy for the participants to intuitively grasp the concepts – words like cooperation, sustainability, and community kept being repeated over and over. Organizers Emily Kawano and Ethan Miller left the workshop reassured that the term “solidarity economy” could easily be explained and easily become a way to bring different groups together. (more information on these workshops, including selected transcripts and videos, is posted at TransformationCentral.org)

On Saturday, after the third and final day of USSF workshops, the second Solidarity Economy caucus was held. Enriched with some new faces, and energized by our first meeting and the content of the workshops, we concretely resolved to found a U.S. Solidarity Economy Network, SEN. We want this network to be a broad tent, linking institutions, networks, and individuals who share the values of the Solidarity Economy. SEN will be a place to exchange practice and theory, to offer support to one another, and to push together for transformation. The existing working group was charged to come up with a more concrete structure, and to plan for a meeting in the summer of 2008.

Through the U.S. Solidarity Economy Network, we will continue the conversations and coalition-building that happened during the workshop sessions. The Solidarity Economy is all about building these connections; reminding us that, amidst our wonderful diversity, we are all related – as members of a society, as parts of an ecosystem, and, potentially, as creators of a new paradigm of economic life based on cooperation and solidarity as well as individuality and freedom. The Solidarity Economy activities at the U.S. Social Forum were an amazing first step at building these connections – bringing together people from all over the country and the world who are engaged in economic transformation in their own communities – and standing on the shoulders of the leaders of the Solidarity Economy movement in Canada and Latin America. The U.S. Solidarity Economy Network can help us further understand how our many ways of working towards economic transformation connect with and complement one another. It can provide us with opportunities to learn from one another as we strive to realize Solidarity Economy values. And, as part of RIPESS, the international solidarity economy network, SEN can help us make our dream of another, possible, solidarity economy a growing and thriving reality in the U.S. and across the world.